If you are reading this because you want to buy a star name, check the IAU Theme Buying Stars and Star Names. Otherwise, please read the text below.

The IAU is keen to make a distinction between the terms name and designation. Throughout this theme, and in other IAU publications, name refers to the (usually colloquial) term used for a star in everyday speech, while designation is solely alphanumerical and used almost exclusively in official catalogues and for professional astronomy.

History of Star Catalogues

The cataloguing of stars has seen a long history. Since prehistory, cultures and civilisations all around the world have given their own unique names to the brightest and most prominent stars in the night sky. Certain names have remained little changed as they passed through Greek, Latin and Arabic cultures, and some are still in use today. As astronomy developed and advanced over the centuries, a need arose for a universal cataloguing system, whereby the brightest stars (and thus those most studied) were known by the same labels, regardless of the country or culture from which the astronomers came.

To solve this problem, astronomers during the Renaissance attempted to produce catalogues of stars using a set of rules. The earliest example that is still popular today was introduced by Johann Bayer in his Uranometria atlas of 1603. Bayer labelled the stars in each constellation with lowercase Greek letters, in the approximate order of their (apparent) brightness, so that the brightest star in a constellation was usually (but not always) labelled Alpha, the second brightest was Beta, and so on. For example, the brightest star in Cygnus (the Swan) is Alpha Cygni (note the use of the genitive of the Latin constellation name), which is also named Deneb, and the brightest star in Leo (the Lion) is Alpha Leonis, also named Regulus.

Unfortunately, this scheme ran into difficulties. Mis-estimates and other irregularities meant it wasn’t always accurate: for example, the brightest star in (the Twins) is Beta Geminorum (Pollux) while Alpha Geminorum (Castor) is only the second brightest star of the constellation. Also, the Greek alphabet only has 24 letters, and many constellations contain far more stars, even if the naming system is restricted to those visible to the naked eye. Bayer attempted to fix this problem by introducing lower-case letters from the modern Latin alphabet (a to z), followed by uppercase letters (A to Z) for the stars numbered 25 to 50 and 51 to 76 respectively in each constellation.

Nearly 200 years after the introduction of Bayer’s Greek letter system another popular scheme arose, known as Flamsteed numbers, named after the first English Astronomer Royal, John Flamsteed. Observing at Greenwich, Flamsteed made the first major star catalogue with the aid of a telescope, published posthumously in 1725. What we now know as Flamsteed numbers were not actually allocated by Flamsteed himself but by a French astronomer, Jérôme Lalande, in a French edition of Flamsteed’s catalogue published in 1783. In this scheme, stars are numbered in their order of right ascension within each constellation (for example: 61 Cygni).

Other designation schemes for bright stars have been introduced, but have not seen the same level of popularity. One such scheme, which built on Flamsteed numbering, was introduced by the American astronomer, Benjamin Gould, in 1879. Only a handful of stars are occasionally referenced with the Gould scheme today — for example, 38G Puppis.

Alphanumeric Designations & Faint Stars

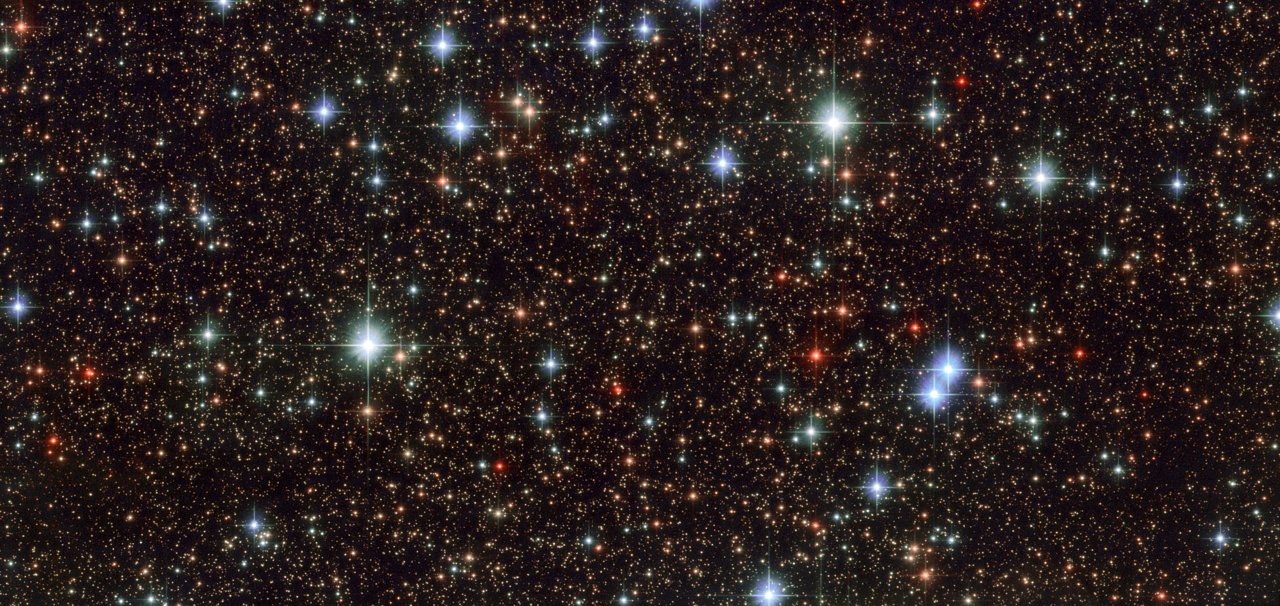

Stars discovered recently will inevitably be much fainter than those catalogued under the Bayer or Flamsteed schemes. As astronomers discover these new stars to study, it is standard practice to identify them with an alphanumeric designation. These designations are practical, since star catalogues typically contain thousands, millions, or even billions of objects, such as that released from ESA’s Gaia satellite.

Several catalogues of faint stars exist and have been around for many years, such as the Bonner Durchmusterung (BD), the Henry Draper Catalogue (HD) and the General Catalogue (GC) of Boss. The BD is supplemented by the Cordoba Durchmusterung (CD) and the Cape Durchmusterung for stars in the southern hemisphere. Other catalogues commonly used are the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory Catalogue (SAO), the Bright Star Catalogue (Harvard Revised Photometry, HR), or the Positions and Proper Motions Catalogue (PPM). The same star can appear in several catalogues, each time with a different designation. As an example, Betelgeuse is known as Alpha Orionis, HR 2061, BD +7 1055, HD 39801, SAO 113271, and PPM 149643.

Binary and Multiple Systems

Stars in binary or multiple systems are labelled in a variety of different ways: by capital letters from the Latin alphabet if the star has a common colloquial name; by Bayer name; by Flamsteed designation; or by a catalogue number. For example, the brightest star in the sky, Sirius, has a white dwarf companion which is catalogued as each of the following: Sirius B, Alpha Canis Majoris B, and HD 48915 B.

Variable Stars

In 1862, a cataloguing scheme for variable stars — those whose brightness appears to fluctuate over time — was proposed by German astronomer, Friedrich Wilhelm Argelander. Proposing to build on Bayer’s scheme, Argelander suggested using the leftover letters R to Z for the variable stars contained in each constellation (and also occasionally Q — for example, in Centaurus, Puppis and Vela).

Initially, the nine available letters seemed more than sufficient to label the small number of variable stars in each constellation. The number of these stars discovered grew, however, and soon Argelander’s scheme was extended to two-letter names, and then to include numbers.

Today, variable stars are catalogued in a few slightly different ways, as a result of their order of discovery. In each constellation, the first variable to be discovered is assigned the letter R and the Latin genitive of the constellation name, such as R Andromedae. The second discovered variable is dubbed S, continuing in this fashion up to Z, following which two-letter names are introduced, such as RR Lyrae. This is followed by RS up to RZ, and then SS to SZ, and so forth up to ZZ. If more variable stars are discovered past this stage, the scheme returns to AA to AZ, BB to BZ and so on, up to QQ to QZ. Interestingly, the letter J is omitted in this scheme to avoid confusion with the letter I.

Such a system provides 334 possible unique designations for variable stars in a constellation. If even more are discovered, the catalogue turns to designations whereby the constellation name is preceded by the letter V and a number, for example, V 1500 Cygni, which can continue indefinitely. The exceptions are those variable stars already assigned a Bayer name, which are not given a new name according to this scheme (such as Delta Cephei, Beta Lyrae, Beta Persei, or Omicron Ceti).

As a further addition, the type of variable star is classified based on a well-known, typical example. Such examples include Mira stars, RR Lyrae stars, or Delta Cephei stars (also known as Cepheids).

Novae and Supernovae

Another slightly different alphanumeric system is used for novae and supernovae, stars that have undergone incredible illumination due to extreme nuclear explosions. Novae are assigned designations according to their constellation, together with the year their superlumination event occurred (e.g. Nova Cygni 1975), and are later given designations based on variable stars. Indeed, Nova Cygni 1975 is the same object as the aforementioned V 1500 Cygni.

Supernovae are also named for their year of occurrence, together with SN and an uppercase letter, such as in SN 1987A. If a single year is particularly flush with supernova events, a double lowercase designation is used (e.g. SN 1997bs).

IAU List of Star Names

In 2016, the IAU mobilised the Working Group on Star Names (WGSN) under its Division C (Education, Outreach, and Heritage), whose purpose was to formally catalogue the names of stars, beginning with the brightest and best-known. The Working Group is composed of an assortment of astronomers from all over the world who bring different perspectives and experience to its decisions. Further details on the establishment of the group can be found in this press release.

Alphanumeric designations are useful for astronomers to officially identify the stars they study, but in many instances, for cases of bright stars, and stars of historical, cultural, or astrophysical interest, it can be more convenient to refer to them by a memorable name. Many such names are already in common parlance, and have been for a long time, but until the establishment of the WGSN there was no official, IAU-approved catalogue of names for the brightest stars in our sky.

The Working Group aims to solve the problems that have arisen over the centuries as different cultures and astronomers gave their own names to stars. Even until recently, some of the most famous stars in the sky — such as Sirius, Rigel and Betelgeuse — had no official spelling, some stars had multiple names, and identical names were sometimes used for completely different stars altogether. As an example, a cursory perusal through historical and cultural astronomy literature finds over 30 names for the star commonly known as Fomalhaut. While this particular spelling has seen the most use over the centuries, similar instances in literature have included Fom-al hut al-jenubi, Fomahandt, Fomahant, Fomal'gaut, Fomal'khaut, Fomalhani, Fomalhut, Formalhaut, Fumahant, Fumahaut, and Fumalhaut. By creating an IAU-endorsed stellar name catalogue, confusion can be reduced. The unique IAU star names will also not be available in the future to name asteroids, planetary satellites, and exoplanets so as to further reduce confusion.

To approve the list of star names, the WGSN is delving into worldwide astronomical history and culture, looking to determine the best-known stellar appellations to use as the officially recognised names. Such an exercise will continue to be the Group’s main aim for the next few years. Beyond this point, once the names many of the bright stars in the sky have been officially approved and catalogued, the WGSN will turn its focus towards establishing a format and template for the rules, criteria and process by which proposals for stellar names can be accepted from professional astronomers, as well as from the general public.

Although there is no rigid format that stellar names must follow — since they have their roots in many varied cultures and languages — the Working Group established some initial, basic guidelines, which build on the lessons from other IAU Working Groups. The guidelines outline a preference for shorter, one-word names that are not too similar to existing names for stars, planets or moons, as well as those that have roots in astronomical and historical cultural heritage from around the world.

Before the establishment of the WGSN, the IAU had only ever officially approved the names of 14 stars, in connection with efforts to catalogue the names of newly discovered exoplanets.